Saturday, March 26, 2005

Something that appeals to the human heart

"There is a powerful need for symbolism, and that means the architecture must have something that appeals to the human heart. Nevertheless, the basic forms, spaces, and appearances must be logical. Designs of purely arbitrary nature cannot be expected to last long."

- Kenzo Tange

Kenzo Tange was the most influential Japanese architect in the second half of the 20th century, and was awarded the 9th Pritzker Prize in 1987. The work of modernist architect Le Corbusier had a profound influence on Tange, who spent 4 years early in his career in the office of Kunio Maekawa, a prominent disciple of Le Corbusier. Following WWII, Tange set up his own studio, which became a proving ground for a generation of talented Japanese architects, including Fumihiko Maki, Kisho Kurokawa and Arata Isozaki.

Tange gained international recognition with his first major commission; he was selected as the architect for the master plan for rebuilding Hiroshima after the atomic bomb was dropped on that city in World War II. At the heart of Tange's design was the Hiroshima Peace Center and Peace Memorial, a combination of traditional Japanese Haniwa tomb and a concrete hyperbolic parabola.

Tange gained international recognition with his first major commission; he was selected as the architect for the master plan for rebuilding Hiroshima after the atomic bomb was dropped on that city in World War II. At the heart of Tange's design was the Hiroshima Peace Center and Peace Memorial, a combination of traditional Japanese Haniwa tomb and a concrete hyperbolic parabola.

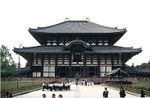

Particularly in his earlier work, Tange drew from the forms of traditional Japanese architecture and reinterpreted them using modern materials and construction techniques. The easily-recognizable temple forms shown above can be seen, transformed, in the concrete and suspended high-tension cable roofs of Tange's stadiums for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In awarding the Pritzker to Tange, the international jury acknowledged this duality in his work: "His stadiums for the Olympic Games held in Tokyo in 1964 are often described as among the most beautiful structures built in the twentieth century. In preparing a design, Tange arrives at shapes that lift our hearts," the citation said, "because they seem to emerge from some ancient and dimly remembered past and yet are breathtakingly of today."

Particularly in his earlier work, Tange drew from the forms of traditional Japanese architecture and reinterpreted them using modern materials and construction techniques. The easily-recognizable temple forms shown above can be seen, transformed, in the concrete and suspended high-tension cable roofs of Tange's stadiums for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In awarding the Pritzker to Tange, the international jury acknowledged this duality in his work: "His stadiums for the Olympic Games held in Tokyo in 1964 are often described as among the most beautiful structures built in the twentieth century. In preparing a design, Tange arrives at shapes that lift our hearts," the citation said, "because they seem to emerge from some ancient and dimly remembered past and yet are breathtakingly of today."In Tange's obituary in the Guardian, Jonathan Glancey wrote:

"The role of tradition," Tange said, "is that of a catalyst which furthers a chemical reaction, but is no longer detectable in the end result. Tradition can, to be sure, participate in a creation, but it can no longer be creative itself."

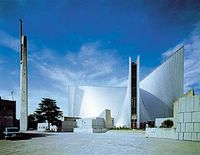

The Cathedral of St Mary, Tokyo (1964), another powerful meeting of historic and contemporary form and structure, both confirms and denies this article of architectural faith. Tange visited several medieval cathedrals before producing his design. "After experiencing their heaven-aspiring grandeur and ineffably mystical spaces," he said later, "I began to imagine new spaces, and wanted to create them by means of modern technology." Which he did, and yet the soaring concrete cathedral is recognisably medieval in inspiration.

As in all medieval - and many modern - cathedrals, the plan of St. Mary's is cross-shaped, with the main entry at the "foot" of the cross, and the altar at the "head." However, the exposed concrete interior, and the concave, rather than convex, shape of the soaring space within, are anything but traditional.

Kenzo Tange died on March 22. He was 91.

Music and Cats

Music and Cats