When most of us in the "developed" world think of "home," the building that comes to mind is one constructed of wood and brick, of steel and concrete. However, according to the

Earth Architecture website, "One half of the world's population, approximately 3 billion people on six continents, lives or works in buildings constructed of earth." Earth building goes by many names: adobe, rammed earth, mud brick, compressed earth. Some types of earth building technologies use cement or other modern building materials for stabilization; others use only combinations of natural, completely biodegradable materials: earth, straw, cactus, manure.

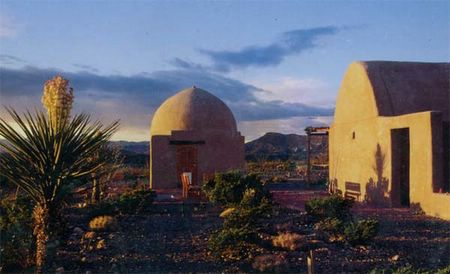

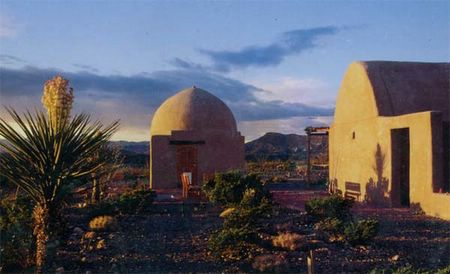

In Presidio, Texas, a small border town in the Big Bend region, a non-profit organization called the

Adobe Alliance is working to increase the population housed in earth buildings, using all-natural adobe. In the 1970's, Alliance founder

Simone Swan apprenticed with Egyptian architect

Hassan Fathy, and was "inspired by his use of earthen materials and his interest in reviving indigenous building techniques for owner-built cooperative housing." When Swan established the Alliance in the late 1990's, she located it in Presidio County in part because of its 37% unemployment rate. Teaching the local population to build homes for themselves and others is part of the Alliance's plan:

The purpose of the Adobe Alliance is to build low-cost energy efficient housing that is climatically and environmentally compatible and to fill widespread needs for sustainable, salubrious housing while enhancing the unique landscape of the Big Bend region of West Texas and other desert environments. Means to reach this goal include:

The use of local renewable, recycled resources and building materials to considerably reduce cost and environmental impact, avoiding the use of industrial materials;

Providing roofs in the configuration of adobe vaults and domes, a unique yet ancient design feature which eliminates the use of wood, an increasingly scarce natural resource;

Designs which harness natural energy for heating and cooling. Adobe walls retain heat in the winter and stay cool in the summer, eliminating the cost of mechanical heating and cooling systems;

A system to meet local housing needs using indigenous skills, thereby providing a source of employment and simultaneously incorporating, preserving and enhancing local architectural heritage.

An appropriate building technique for chemically sensitive individuals, using only materials that are totally non-toxic.

This

article in the

Desert-Mountain Times described a hands-on workshop held by the Alliance in February:

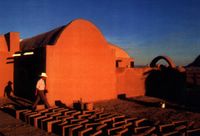

On a mesa a few miles east of this border town, a dozen men and women scooped up handfuls of mud and hurled them at the sides of a small adobe building. They stepped back, admired the sound and effect of mud hitting the wall, and reached for another helping. It bothered no one that the secret ingredients in the mud were prickly pear cactus and fresh horse manure that had been cold-brewed in a "tea" before being mixed with earth and straw.

One young man leapt as though making a game-winning lay-up and, plop, hit his target about 10 feet up the wall. His friends cheered.

The walls werent the only thing affected by their enthusiasm. Their hair and clothing were becoming spattered in the process. No one seemed to care. Indeed, they expected it. This was part of what the participants paid $250 to $300 each to do.

The mud-throwing men and women spent a long weekend last month at the seventh annual Adobe Alliance workshop three days of education on what to do and how to do it for an increasingly popular form of building. Some got their first taste of building with adobes; others honed their skills.

The rest of the article is here. Rather than focusing on the upscale housing market in such places as the Albuquerque-Santa Fe-Taos axis in New Mexico or the wealthier areas of Arizona or California, the alliance is in the forefront of a renewed effort to build energy-efficient housing using materials that considerably reduce the cost and the impact on the environment.

"Its all in the spirit of building with local people and local materials," said Simone Swan, who founded the alliance and whose home was the workshop classroom and laboratory. "Its all economic incentives because dirt is the only (building material) that is not linked to the price of oil," said Swan, who studied use of earthen materials and indigenous building techniques under Hassan Fathy, a renowned environmental architect.

The project was under the watchful eyes of Maria Jesus Jimenez, who managed the sessions; Joaquin Valenzuela, an adobe vault and dome craftsman; and Efren Rodriguez, a master adobe plasterer. All hailed from Ojinaga, Mexico, across the Rio Grande from Presidio.

That mornings assignment was to replaster the walls of a 12-by-12-foot domed adobe building that is a guest quarters for Swans 1,600-square-foot adobe home. The smaller building originally was plastered with a cement-based covering - a move Swan said was a mistake. Unusually heavy rains last summer produced hairline cracks in the plaster, and they could not be patched. So the old plaster was peeled off the walls, broken into small chunks and recycled as walkways around the yard - blue paint and all.

This time, Swan said, the plaster would be based on the cactus-and-horse-manure mixture instead of commercial cement. The prickly pear pads were cut open and then soaked for three days in water, which produced a syrup like consistency that helped the mud adhere to the adobe blocks. The manure soaked separately for three days, and unlike the cactus liquid, it was poured through a wire mesh strainer before the liquid was added to the dirt in the mixing process. "The fresher, the better," Swan said of the manure. "Go put a bucket right under the horse."

After slinging the mud on the bare adobe blocks, workers smoothed the mixture over the surface and stuffed extra between the blocks to fill voids left by removing the cement-based plaster.

As he worked the mud with his hands, Richard Hinkle of Alpine said, "Im reverting to my childhood. This is where my expertise lies." Katje Erickson, an environmental planner and engineer from Belen, N.M., agreed with that notion: "Ive been in the studio too much and in front of a computer too much. I had to get out and get my hands dirty."

John Morony, who teaches environmental biology at Southwest Texas Junior College in Del Rio, said he was learning much of what he would need to know when he begins work on his own house in May. It will be built of smoother compressed-earth blocks instead of traditional adobes, he said, but the process is much the same. "Im seeing what I want to build a house with," said Morony, who is a member of the Adobe Association of Del Rio. The group, he said, "teaches people to build with whats available and thats dirt."

He gave as well as he received from the session. During an after-lunch discussion among the workshop attendees, he explained how adobe blocks help keep a building cool in the summer and warm in winter by absorbing and then releasing moisture in the air as needed. A well-built adobe house can be as much as 20 degrees cooler in summer than the air outside, he said.

Others at the workshop included Nripal Aghikary, a native of Nepal who is attending college in El Rito, N.M.; Fernando Pina Rodriguez, an engineer from San Luis Potosi, Mexico; Robert Dinoir of Del Rio, who described his design for a cooling tower for adobe buildings; and three students doing graduate work in architecture at the University of Texas: Ann Tucker, Nick Brinen and Jack Sanders.

Later in the afternoon, when Jimenez and her crew had left for the day, the workshop participants tried their hand at mixing mud from the same recipe to test themselves on what they had learned. They started the cement mixer and began measuring and adding ingredients. Sanders scooped out some of the freshly churned mud, hurried to the building and hurled the gooey mixture at a bare spot on the wall.

"It sticks!" he shouted. The rest of the mud was dumped into a wheelbarrow and taken to the side of the building where the others grabbed the mixture and began smoothing it over the adobe blocks.

For more information, contact www.adobealliance.org or write to Adobe Alliance, 1 Casa Piedra Road, Presidio, TX 79845.

<- Close Reading the article, I immediately wanted to sign up for a workshop. Never mind that adobe is not a suitable building material for the Pacific Northwest. I've always loved playing in the mud. Imagine putting that childlike pleasure to such a very good use.

This article in the Desert-Mountain Times described a hands-on workshop held by the Alliance in February:

This article in the Desert-Mountain Times described a hands-on workshop held by the Alliance in February:

Music and Cats

Music and Cats