Philip Johnson was one of the first architects whose work I remember. I grew up in Houston in the 1960's and 1970's, in the period during which Philip Johnson was changing that city's skyline for the better. I might not have paid attention to Johnson's work at that time, however, had it not been for my architect father, who was always saying, "Look! Look at that."

, Johnson said in a 1991 interview, "Houston is undoubtedly my showcase city. I saved all my best buildings for Houston." Here are a few of those buildings:

, a small Houston college, was Johnson's second Houston commission. (His first was the house he designed for Dominique and John de Menil. Finished in 1951, it was the first flat-roofed modern house in its wealthy River Oaks neighborhood.) Built in the mid-1950's, the campus is a modernist take on Thomas Jefferson's plan for the University of Virginia, with brick and glass academic buildings connected by black steel-framed covered walkways on either side of an open lawn. Whereas the library was the focal point of

, at St. Thomas the focus is the

. Part of the original campus plan, the chapel was not built until 1997... by which time Johnson's design sensibilities had changed dramatically. The chapel was Johnson's last work in Houston.

Pennzoil Place, completed in 1976, was the first of Johnson's great Houston skyscrapers. It's the modernist glass box with a twist. Two mirror-image 36-story towers, trapezoidal in plan, are located on their site to create triangular atrium lobbies with sloping glass roofs. The tops of the towers are similarly sloped, but in opposite directions. The two towers are separated by a 10-foot-wide vertical slot; from some locations they appear as two towers, from others as only one. In 1983, the RepublicBank Center went up across the street from Pennzoil. Only someone who had followed Johnson's career in the intervening nine years would have believed them to be the work of the same architect. Clad in red Swedish granite, with crenelated towers reminiscent of Dutch gabled townhouses, and two large steps in its massing, the RepublicBank building was unabashedly historical in style. It's rumored RepublicBank steps back as it does so as not to hide Pennzoil Place on the skyline. The composition created by these two radically different buildings is a particular favorite of mine.

Completed in 1984, Transco is my favorite skyscraper in Houston. Its 64-story form looks like a depression-era stone skyscraper cast in glass. There are no other tall buildings around it, so its skin mirrors the sky, and its color changes constantly throughout the course of the day. As Houston is a flat city, Transco is visible for a great distance; occasionally a view of the top of the tower will appear when one least expects it.

When Johnson received the first Pritzker Prize in 1979, he expressed his hope that architecture might one day again be considered fundamental to our society: "Yet

. Values can change. Art, myth, religions can bloom once again. We may, for example, want to rebuild America. We surely can if we want to. We can do anything. We have the skill, the materials, the labor force. Heaven knows, we have the need: our ugly surroundings, our inadequate housing, our sad slums are testimony. We can, if we but will; architecture, as in all the world’s history, could be the art that saves."

On Wednesday, January 25, Philip Johnson died at home in New Canaan, CT, in the Glass House that he designed and built for himself in 1949. At 98, he had a life that was longer than most. He is survived by his art - the built legacy of more than 50 years of architectural practice - and by the influence that he had on more than one generation of architects.

Update: Paul Goldberger has a fine article on Philip Johnson in the January 27 New York Times. Since it will become pay-per-view in just a few days, I've included the full text of it

Philip Johnson Is Dead at 98; Architecture's Restless Intellect

By PAUL GOLDBERGER

Published in the New York Times, January 27, 2005

Philip Johnson, at once the elder statesman and the enfant terrible of American architecture, died Tuesday at the compound surrounding the Glass House, the celebrated residence he built for himself in New Canaan, Conn. He was 98.

His death was disclosed by David Whitney, his companion of 45 years.

Often considered the dean of American architects, Mr. Johnson was known less for his individual buildings than for the sheer force of his presence on the architectural scene, which he served as a combination godfather, gadfly, scholar, patron, critic, curator and cheerleader. His 90th birthday, in July 1996, was marked by symposiums, lectures, an outpouring of essays in his honor and back-to-back dinners at two venerable New York institutions he had played a major role in creating: the Museum of Modern Art, whose department of architecture and design he joined in 1930, and the Four Seasons restaurant, which he designed as part of the Seagram Building in 1958.

His long career was a study in contradictions. He first became famous as an impassioned advocate of Modern architecture, and his early writings helped establish the reputation of European Modernists like Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius in this country. He began his architectural career as Mies's leading acolyte. But what fascinated him most was the idea of the new, and once he had helped establish Modernist architecture in the United States, he moved on, experimenting with decorative Classicism, embracing the reuse of historical elements that would become known as postmodernism, and finally returning again to Modernism, yet one with an expressive and highly emotional energy.

Mr. Johnson's own architecture received mixed reviews and often startled the public and his fellow architects. Because of his frequent changes of style, he was often accused of pandering to fashion and of designing buildings that were facile and shallow. Yet he created several designs, including the Glass House, the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art, and the pre-Columbian gallery at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington that are widely considered among the architectural masterworks of the 20th century. And for his entire career, his engagement with architectural theory and ideas was as deep as that of any scholar.

He was the first winner of the Pritzker Prize, the $100,000 award established in 1979 by the Pritzker family of Chicago to honor an architect of international stature. In 1978, he won the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects, the highest award the American profession bestows on any of its members.

As an architect, he made his mark arguing the importance of the aesthetic side of architecture and claimed that he had no interest in buildings except as works of art. Yet he was so eager to build that he willingly took commissions from real estate developers who refused to meet his aesthetic standards. He liked to refer to himself, with only some irony, as a whore. And in the 1930's, this man who believed that art ranked above all else took a bizarre and, he later conceded, deeply mistaken detour into right-wing politics, suspending his career to work on behalf of Gov. Huey P. Long of Louisiana and later the radio priest Father Charles Coughlin, and expressing more than passing admiration for Hitler.

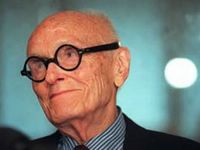

Mr. Johnson's foray into fascism was over by the time the United States entered World War II, and in the mid-1950's he sought to publicly atone to Jews by designing a synagogue in Port Chester, N.Y., for no fee. But to the end of his life the contradictions continued. With his dignified bearing and elegant, tailored suits, he looked every bit the part of a distinguished, genteel aristocrat, but he played the celebrity culture of the 1980's and 90's as successfully as a rock star. To the public, he was far and away the best-known living architect, and his crisply outlined, round face, marked by heavy, round black spectacles of his own design, was a common sight on television programs and magazine covers.

Except for his brief involvement in right-wing politics, all of his careers revolved around architecture. He began his professional life as a writer, historian and curator and did not enter architecture school until he was 35. Even when he became one of the nation's most eminent practicing architects, he continued to be a major patron of institutions and of younger architects, whose work he followed with avid interest.

He began his career as an ardent champion of Modernism, but unlike many of the movement's early proselytizers, he changed with the times, and his own work showed a major movement away from beginnings that were heavily influenced by Mies. In the late 1950's, just after he had collaborated with Mies on the Seagram Building on Park Avenue, he introduced elements of classical architecture into his buildings, beginning a long quest to find ways of connecting contemporary architecture to historical form. It was a quest that would begin with highly abstracted versions of Classicism in the 1960's and culminate in a much more literal use of the architectural forms of the past in his revivalist skyscrapers of the 1980's.

That phase of Mr. Johnson's career included such well-known monuments as the classically detailed pink-granite AT&T Building (now the Sony building) on Madison Avenue, which he completed in 1984 with John Burgee, then his partner; the Republic Bank tower (now NCNB Center) in Houston, which used elements of Flemish Renaissance architecture; the Transco Tower (now the Williams Tower) in Houston, which recapitulated the setback forms of a romantic 1920's tower in glass, perhaps his finest skyscraper; and the PPG Place in Pittsburgh, a reflective glass tower whose Gothic form copied the shape of the tower of the Houses of Parliament in London.

Focusing on Historical Form

Institutional clients also received their share of Mr. Johnson's fixation with historical form: he designed a Romanesque structure in brick for the Cleveland Play House and a Classical building based on the designs of the French visionary architect Étienne-Louis Boullée for the architecture school of the University of Houston.

In the late 1980's Mr. Johnson's restless mind, having played a major role in shifting American architecture toward postmodernism, with its reuse of traditional elements, moved on yet again. Fascinated by the intense, highly abstract work of a group of younger Modernist architects who were to become known as the deconstructivists, Mr. Johnson began to incorporate elements of their architecture into his own work.

He was particularly entranced with the buildings of the Los Angeles architect Frank Gehry, whose complex, seemingly irrational forms would appear to be the antithesis of the cool, rational, ordered architectural world of Mr. Johnson's first mentor, Mies, and much of his late work reflected Mr. Gehry's influence.

Mr. Johnson, an urbane, elegant figure, was perhaps the most socially prominent New York architect since Stanford White. Born to wealth, he and Mr. Whitney, a curator and art dealer, lived well, for many years in a town house on East 52nd Street that Mr. Johnson had originally designed as a guest house for John D. Rockefeller 3d, then in an elaborately decorated apartment in Museum Tower above the Museum of Modern Art and always on weekends in the famous Glass House compound.

Mr. Johnson had lunch daily amid other prominent and powerful New Yorkers at a special table in the corner of the Grill Room of the Four Seasons. His guest was likely to be a young architect in whose work he had taken an interest, and for years his table functioned as a kind of miniature architectural salon.

In the evenings, he was frequently seen at exclusive social events, for years by himself and in the last decade, as he felt greater ease in making his relationship with Mr. Whitney public, with his companion. He was among the few architects whose comings and goings were considered worthy of notice in the gossip columns.

He had been an active art collector since the days when, as a student traveling in Germany, he bought a pair of Paul Klees from the artist. Eventually he came to be a collector of contemporary art: advised by Mr. Whitney, he filled his walls with paintings by Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns when they were just gaining public attention, and he amassed one of the most complete collections of paintings by Frank Stella in private hands.

Mr. Johnson not only lived and ate in places of his own design, he also worked in them. For many years his office was in the Seagram Building. Mr. Johnson practiced alone there for some years, then collaborated with the architect Richard Foster, for a time, and in 1967 formed a partnership with John Burgee.

It was this partnership that transformed Mr. Johnson from a scholar-architect designing small to medium-size institutional buildings for well-to-do clients into a major force in commercial architecture. Mr. Burgee's arrival coincided with the firm's movement toward a number of major, widely acclaimed skyscraper projects, including the IDS Center in Minneapolis and Pennzoil Place in Houston. Mr. Johnson's leanings were always toward the aesthetic issues in design, and in Mr. Burgee he had a partner who could serve not only as a colleague in design but also as an executive overseeing the kind of large architectural office required to produce major skyscrapers.

As if to mark Mr. Burgee's role, the Johnson-Burgee firm moved in 1986 into the elliptical skyscraper at 885 Third Avenue, between 53rd and 54th Streets. Popularly known as the Lipstick Building, it had been designed by the partners together. But the partnership was not to last long beyond the move: Mr. Burgee, eager to occupy center stage, negotiated a more limited role for Mr. Johnson and in 1991 exercised the prerogative he had as the firm's chief executive and eased Mr. Johnson out altogether.

It proved an unwise decision: the firm, crippled by an arbitration decision unrelated to Mr. Johnson, soon went into bankruptcy, all but ending Mr. Burgee's career. Mr. Johnson, who had severed ties to his former firm, had no liability and went on to rent a smaller space in the Lipstick Building, gleefully hanging out his shingle in his mid-80's and declaring himself in business as a solo practitioner. Before long, he had several commissions, including a cathedral in Dallas, and his career had recharged itself.

Philip Cortelyou Johnson was born on July 8, 1906, in Cleveland, the son of Homer H. Johnson, a well-to-do lawyer, and Louise Pope Johnson. Supported by a fortune that consisted largely of the Aluminum Company of America stock given him by his father, Mr. Johnson went to Harvard to study Greek, but became excited by architecture and spent the years immediately after his graduation in 1927 touring Europe and looking at the early buildings of the developing Modern architecture movement.

He teamed up with Henry-Russell Hitchcock, at that time the movement's chief academic partisan in the United States, and their travels together resulted in their book "The International Style," published in 1932 and now a classic. "We have an architecture still," is how Mr. Johnson and Mr. Hitchcock concluded the book, which played a major role in introducing Americans to the work of European Modernists like Mies, Gropius and Le Corbusier, then barely known here.

In 1930, Mr. Johnson joined the architecture department at a new institution in New York, the Museum of Modern Art. He moved the museum quickly to the forefront of the architectural avant-garde, sponsoring exhibitions on contemporary themes and arranging for visits by Gropius, Le Corbusier and Mies, for whom he also negotiated his first American commission.

Mr. Johnson left the museum in 1936 to pursue his political agenda, dividing his time among Berlin, Louisiana and his family's home in Ohio. By the summer of 1940, his infatuation with right-wing politics had faded, although as Franz Schulze, his biographer, wrote in 1994, it was never clear whether he withdrew because he had changed his mind or because he had failed to achieve political success. "In politics he proved to be a model of futility," Mr. Schulze wrote in "Philip Johnson: Life and Work. "He was never much of a political threat to anyone, still less an effective doer of either political good or political evil."

In 1941, at 35, Mr. Johnson turned once and for all to the field that would occupy him for the rest of his life and enrolled at the Harvard Graduate School of Design to begin the process of becoming an architect.

At Harvard, Mr. Johnson did what few students, even those of great means, have been able to do: he actually built the project he designed as a thesis. It was a house in the style of Mies, its lot surrounded by a wall that merges into the structure, and it still stands at 9 Ash Street in Cambridge, Mass.

After wartime service in the United States Army - the F.B.I. had investigated Mr. Johnson for his fascist leanings, but the government decided he was sufficiently repentant to wear the uniform (he never saw combat) - he returned in 1946 to the Museum of Modern Art. At the same time he began to slowly build up an architectural practice of his own, combining it with his career as a writer and curator.

He designed a small, boxy house, also highly influenced by Mies, for a client in Sagaponack, Long Island, in 1946, but his first significant building, and still perhaps his most famous, was not for another client at all but, like the Cambridge house, for his own use: it was the Glass House in New Canaan, completed in 1949 with its counterpoint, a brick guest house.

The serene Glass House, a 56-foot-by-32-foot rectangle, is generally considered one of the 20th century's greatest residential structures. Like all of Mr. Johnson's early work, it was inspired by Mies, but its pure symmetry, dark colors and closeness to the earth marked it as a personal statement: calm and ordered rather than sleek and brittle.

A Home Becomes a Museum

Over the years, Mr. Johnson added to the Glass House property, turning it into a compound that became a veritable museum of his architecture, with buildings representing each phase of his career. A small, elegant white-columned pavilion by the lake was built in 1963; an art gallery, an underground building set into a hill, with pictures from Mr. Johnson's extensive collection of contemporary art set on movable panels, in 1965; the sculpture gallery of 1970, a sharply defined, irregular white structure covered with a greenhouselike glass roof; a library of stucco with a rounded tower that from a distance looks like a miniature castle (1980); a concrete-block tower, as much a piece of sculpture as a building, dedicated to his lifelong friend Lincoln Kirstein, the writer and New York City Ballet co-founder (1985); a "ghost house" of chain-link fence, honoring Mr. Gehry, who often used this material (1985); and finally, what Mr. Johnson called "Da Monsta," an irregularly shaped building of deep red with sharply curving walls, finished in 1995.

The "Monsta" -he could not quite bring himself to call one of his buildings a monster, but said its shape resembled it - is set at the gate of the estate and was intended to serve as a visitors center once the public was admitted to the property after his death. The compound was willed to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which plans to run it as a museum.

In addition to Mr. Whitney, Mr. Johnson is survived by a sister, Jeannette Dempsey, now 102, of Cleveland.

After the Glass House was completed in 1949, Mr. Johnson received other residential commissions, including a number of houses in New Canaan. His first work on a very large scale, however, was the Seagram Building, designed with Mies. The deep bronze Seagram is considered by many critics to be the finest postwar skyscraper in New York.

But by then, Mr. Johnson was growing impatient with the limitations of the strict, austere Miesian vocabulary. He began to explore a more decorative sort of neo-Classicism, leading to designs like the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth (1961), the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center (1964) and the Bobst Library at New York University, designed in 1965 but not completed until 1973. His work in that period led the architectural historian Vincent Scully to refer to him as "admirably lucid, unsentimental and abstract, with the most ruthlessly aristocratic, highly studied taste of anyone practicing in America today."

"All that a nervous sensibility, lively intelligence and a stored mind can do, he does," Mr. Scully said.

Mr. Johnson's art collecting brought him a nearly continuous stream of commissions to design museums, and his ties to the Museum of Modern Art brought him the request to design the museum's 1951 and 1964 expansions beyond its original 1939 building, including the sculpture garden. He also designed the original Asia House gallery on East 64th Street, now the Russell Sage Foundation, as well as museums in Fort Worth; Utica, N.Y.; Lincoln, Neb.; and Corpus Christi, Tex.

Despite his record as a museum designer and his long association with the Modern, the museum's board, of which Mr. Johnson was a member, decided in 1978 to hire a different architect to design its new west wing. The job went to Cesar Pelli, and Mr. Johnson was deeply hurt.

For some time, relations cooled between him and the museum he had supported nearly since its founding, but eventually they resumed, and Mr. Johnson and Mr. Whitney moved into the apartment tower above the museum designed by Mr. Pelli. In 1984, as a tribute to Mr. Johnson as its founding curator, the museum's department of architecture and design named its exhibition space the Philip Johnson Gallery. And the Modern observed Mr. Johnson's 90th birthday with a pair of exhibitions: one of notable works of art that the architect had donated to the museum, and another of works given by architects in Mr. Johnson's honor. More recently, the architect Yoshio Taniguchi set to work on his design for the Modern's latest expansion, Mr. Johnson met occasionally with him to chat about the challenges of blending old and new.

The beginnings of his late career as a major commercial architect were not in New York, however, but in Minneapolis, through an immense project in 1972 for Investors Diversified Services, a financial conglomerate now part of American Express. A square-block complex containing a roughly octagonally shaped, 51-story glass tower, hotel and retail wing placed around a central glass-covered court, the design blended Mr. Johnson's interest in angular forms with a sensitive urbanism. It quickly became a focal point for downtown Minneapolis and was the first of a generation of what might be called social skyscrapers: towers that did not merely house office workers but also contained myriad public spaces.

Among the many observers impressed by the tower was Gerald D. Hines of Houston, a real estate developer who had begun his career as a builder of warehouses but who by the early 1970's had sought to make a mark with much larger buildings by prominent architects. Mr. Hines hired Mr. Johnson and Mr. Burgee to design Pennzoil Place, a twin-towered complex of glass in downtown Houston that was completed in 1976. One of the most widely known skyscrapers in the country, Pennzoil Place consists of two trapezoidal towers placed so as to leave two triangular areas open on the site. These areas were covered with steel and glass trusses to create greenhouselike lobbies; as a further formal gesture, each tower was given a slanted roof for the top seven floors.

Pennzoil Place would prove widely influential, but five years later Mr. Johnson and Mr. Burgee moved away from it with the design for one of the most startling skyscrapers of the last generation, the AT&T headquarters in New York, the so-called "Chippendale skyscraper" with a split pediment resembling an antique highboy.

During the 1980's Mr. Johnson and Mr. Burgee also designed major skyscrapers in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco and Dallas, many for Mr. Hines. Most of them, following the lead of the AT&T. Building, were lavishly finished in granite and marble and imitated some aspect of architecture of the past.

Mr. Johnson also designed the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, Calif., and the Museum of Television and Radio on West 52nd Street in New York. With Mr. Burgee, he produced plans through the 1980's for office towers for Times Square. Widely criticized, they were never built. After the dissolution of his partnership with Mr. Burgee, he formed one with Alan Ritchie, a longtime associate, and produce several works for Donald J. Trump, including the glass tower at 1 Central Park West and projects for the Riverside South residential development; and plans for a cathedral for a gay congregation in Dallas. Mr. Johnson continued to go to work at Philip Johnson/Alan Ritchie Architects in the Seagram Building as recently as last year.

Though he gave up formal scholarship when he became an architect, he continued to write and lecture frequently. His constant theme, unchanged through all his stylistic variations, was his belief in the need to view architecture as an art, separating him from the socially minded early Modernists whose cause he once championed so ardently.

In a famous lecture in 1954 at Harvard titled "The Seven Crutches of Modern Architecture," he said, "Merely that a building works is not sufficient." Later, in an oft-quoted remark, he said, "I would rather sleep in Chartres Cathedral with the nearest toilet two blocks away than in a Harvard house with back-to-back bathrooms."

Years later, Mr. Johnson told an audience: "We still have a monumental architecture. To me, the drive for monumentality is as inbred as the desire for food and sex, regardless of how we denigrate it."

But he ended by arguing: "Monuments differ in different periods. Each age has its own.

"Maybe, just maybe, we shall at last come to care for the most important, most challenging, surely the most satisfying of all architectural creations: building cities for people to live in."

All done!

Philip Johnson was one of the first architects whose work I remember. I grew up in Houston in the 1960's and 1970's, in the period during which Philip Johnson was changing that city's skyline for the better. I might not have paid attention to Johnson's work at that time, however, had it not been for my architect father, who was always saying, "Look! Look at that."

Philip Johnson was one of the first architects whose work I remember. I grew up in Houston in the 1960's and 1970's, in the period during which Philip Johnson was changing that city's skyline for the better. I might not have paid attention to Johnson's work at that time, however, had it not been for my architect father, who was always saying, "Look! Look at that."

On Wednesday, January 25, Philip Johnson died at home in New Canaan, CT, in the Glass House that he designed and built for himself in 1949. At 98, he had a life that was longer than most. He is survived by his art - the built legacy of more than 50 years of architectural practice - and by the influence that he had on more than one generation of architects.

On Wednesday, January 25, Philip Johnson died at home in New Canaan, CT, in the Glass House that he designed and built for himself in 1949. At 98, he had a life that was longer than most. He is survived by his art - the built legacy of more than 50 years of architectural practice - and by the influence that he had on more than one generation of architects.

Music and Cats

Music and Cats